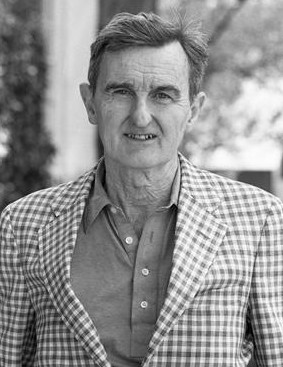

Edward Ashton Nickerson

July 1, 1925 ~ January 1, 2026 (age 100)

Edward Ashton "Nick" Nickerson, who founded the University of Delaware’s journalism program, died on New Year’s Day in Sharon, Connecticut. He was 100.

Nick started the journalism program in 1970 and led it for 21 years. At first, he had little help and taught everything from basic news reporting to radio writing, in addition to advising the university's student newspaper. His office in the university’s Memorial Hall symbolized the status of the program and his position. It was in the basement, next to the men’s room, and windowless. He hired more professors, found working journalists to teach part-time, such as famed Philadelphia Daily News columnist Chuck Stone, and built the program.

He enjoyed teaching more than anything. The first time he set foot in a classroom, he recalled, he knew he was in the right place. He was known as a lively instructor and had a tradition of jumping on top of his desk in one bound, something he could still do in his 60s. He issued critiques called “boos and bouquets.” Trying to drill into students the importance of telling readers where information came from (for example, “Smith said” or “according to Johnson”), he made up a rhyming tune. When ex-students held an online reunion with him in 2025 after he turned 100, they remembered the “Attribution Song.”

Above all, he believed in the importance of honest journalism. He refused to put political bumper stickers on his car, fearing that as the student paper’s adviser, he might taint the paper’s neutrality. He exhorted them to believe in the role of the press, urging them to “keep the faith.”

David Hoffman, a 1975 Delaware grad who went on to report for the Washington Post and win two Pulitzer Prizes, saluted Nick in 2025 for his birthday. He recalled writing a controversial story and taking a paper copy to Nick’s Newark home one evening before deadline. The professor held it in his hands with a pencil and pored over every line. “You were selfless, wise, patient, and encouraging,” Hoffman wrote. “I hope you have long forgotten my story but will never forget how vital your teaching and mentoring was to a generation of students.”

Another U. of D. journalism student, Blake Wilson, went on to become editor of Newark’s Weekly Post, then head of the Mississippi Economic Council. He counted six Pulitzer Prize winners educated during Nickerson’s decades. Countless other Nickerson students stayed close to home and joined the News Journal staff, including reporter Val Helmbreck, food critic Al Mascitti, and sports reporter Kevin Tresolini. “It started for all of us with your vision as an English professor working from a small office, but thanks to your persistence and leadership, a thriving program now is available at the UD—a true legacy,” Wilson wrote.

Nickerson sometimes taught English and American literature classes, including detective fiction. His love of teaching surfaced when he taught the Dashiell Hammett novel The Maltese Falcon. Recreating a famous scene, Nickerson had another professor don a trench coat, tumble into his classroom, fall apparently dead, then let slip from his hands the mysterious falcon statue! He retired but never forgot the U. of D. In his old age, he endowed a lecture fund to bring reporters to speak on campus.

Nick was born July 1, 1925, in Wilmington, the son of a DuPont Company executive, Elgin Nickerson, and his wife, Margaret Pattison Nickerson. He spent most of his boyhood in Fairfield, Connecticut, and Newburgh, New York. He grew up with his older sister, Roma, and attended the local public elementary schools. Because Nick suffered from asthma, his parents sent him to boarding schools in the mountains during his teenage years.

For one year, he had the unusual experience of going to a boys’ school at Mohonk Mountain House, a grand hotel on a mountain lake in New Paltz, New York. The owners, the Smiley family, taught classes and housed the boys in the hotel rooms. In the afternoons, the boys would swim, hike, ski, skate, or work around the property. He loved the school and talked about it for the rest of his life.

He went on to graduate from Northwood School in Lake Placid, New York, near the site of the 1932 Winter Olympics. He was on the ski team and ski jumped (the latter of which left him with nightmares!).

In 1943, Nick joined the 10th Mountain Division—the first American ski troops—and fought in the Apennine Mountains of Italy in 1945. He was awarded the Silver Star for, in the words of the Army, “gallant conduct under fire” and “disregard for his own safety to save the lives of his comrades.” Decades later, another University of Delaware English professor, McKay Jenkins, wrote a book about the 10th Mountain Division called The Last Ridge, and quoted Nick.

After the war, he attended Dartmouth College, where he wrote for the student paper, helped edit the literary magazine, and graduated with an English degree in 1949. He landed a job as a reporter for the Rutland Daily Herald in Vermont, then was hired by the Associated Press wire service. While assigned to the AP’s Baltimore bureau, he met Liselotte “Bee” Davis, a college student and native of Baltimore. After her graduation, they married on September 16, 1955, and moved to New York City when he was transferred to AP’s headquarters there.

After spending the 1950s in journalism, he switched to teaching. In the 1960s, he taught English at three boarding schools. He became chair of the English department at the Emma Willard School in Troy, New York, a girls’ school that his mother and other family members had attended.

Nick became interested in teaching at the university level and earned a Ph.D. in English at the State University of New York in Albany. He combined his English teaching and newspaper experience to become the first director of the University of Delaware journalism program, which was part of the English department.

He retired as a university professor in 1991. He and Bee moved to Lakeville in the Northwest Corner of Connecticut. He taught extension classes on literature through the Taconic Learning Center, joined book clubs, sang in a barbershop group, and cross-country skied for years.

After nearly 52 years of marriage, Bee died of cancer in 2007. Nick moved to a retirement community nearby, where he was a friendly fixture for years.

He celebrated Christmas with his family in 2025 then, days later, entered Sharon Hospital in Connecticut with pneumonia that led to a heart attack and congestive heart failure. On New Year’s Day 2026, at age 100 years, six months, he died as his daughter read him a poem by John Keats, “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.”

Nick loved chatting up strangers, savoring a good meal with wine, reading, playing chess, learning new things, skiing, traveling, concertgoing, wordplay, spending time with friends and family, and almost anything Italian. Days before his death, he asked his son to take him out to his favorite restaurant for dinner.

Survivors include his daughter, Louisa, of Bethesda, Maryland, and her partner, David Shelton; his son, Matthew, daughter-in-law, Elizabeth, and grandchildren, John and Julia, all of Chicago; a niece, Anne Hockmeyer Brown; a nephew, Brian Hockmeyer, and Brian's wife, Ann. Nick's sister, Roma Nickerson Hockmeyer, died in 1981.

A memorial service will be held at the Congregational Church of Salisbury, Connecticut, on Saturday, February 14, at noon. A reception will follow.

Edward A. Nickerson Obituary

1/15/2026